about

Leyla Vural. Click here for my CV.

Everyone has a story, and I have always loved to listen to the rich tapestry of experience that people share if given the chance. That’s why after more than 20 years in the labor movement, I returned to school to earn an M.A. in oral history at Columbia University. I wanted to learn the newest methods in the oldest of traditions: listening. Today, I conduct unhurried, open-ended interviews, edit those interviews into shareable stories, and, although based in New York City, am a community affiliate of the Centre for Oral History and Digital Storytelling at Concordia University in Montreal.

My oral history work includes interviews with the sculptor John Pai about creativity; with community leader Karl Rodney, cofounder of The New York Carib News, about challenging systemic racism and getting caught in its throes; with recipients of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine and other pre-eminent scientists at The Rockefeller University about discovery; with trade unionists about the workers’ rights movement; with LGBTQ New Yorkers about life before and after the 1969 Stonewall Uprising; and with neighborhood activists about preserving sites of cultural importance in working-class communities and communities of color.

John Pai’s oral history is featured in “Eternal Moment,” a retrospective of his work at the Korean Cultural Center of New York, and in the book “Liquid Steel,” published by Rizzoli. The short films I wrote and produced from my interviews with scientists are available online. Some of my work is available in the archives at Columbia University, Cornell University, The LGBT Community Center in New York, the New-York Historical Society, The Rockefeller University, and soon at the Archives of American Art at the Smithsonian. A paper I wrote about Hart Island (New York City’s potter’s field, or public graveyard) was the public history essay in the Oral History Society journal. And the Hannah Arendt Center for Politics and Humanities at Bard College selected my piece on ethical listening as a “favorite essay.” I have given talks and conducted workshops in Belfast, Glasgow, Montreal, New York and Beijing (remotely).

Oral history is, to me, a small “d” democratic exercise. The very act of listening attentively to people, be they what Studs Terkel called “the etceteras” or leaders in their fields, recognizes that we’re all makers of history with something worthwhile to share. One of the things I love about oral history is that it’s communal. By definition, you can’t work alone if your work is about listening to people. In this way, oral history mirrors all efforts at social change and, of course, life itself. It’s not only better with other people, it’s impossible without them. Life stories can nurture empathy and help us build a shared vision for the future. They can be instruments of insight into what a place, time, or set of ideas were once like. They can be a record of change. And no matter how hard things may have been, by capturing the full scope of a person’s life, they also can be a record of good times and, even, fun.

On the subject of fun, I was the storyteller at a conference at the U.N. on sustainable energy, and for three years I was an interviewer for The Civilians, which creates plays from interviews. I have a Ph.D. in geography from Rutgers University and, with funding from the National Science Foundation, used union records to look at the community orientation of the garment workers' unions in 20th-century New York.

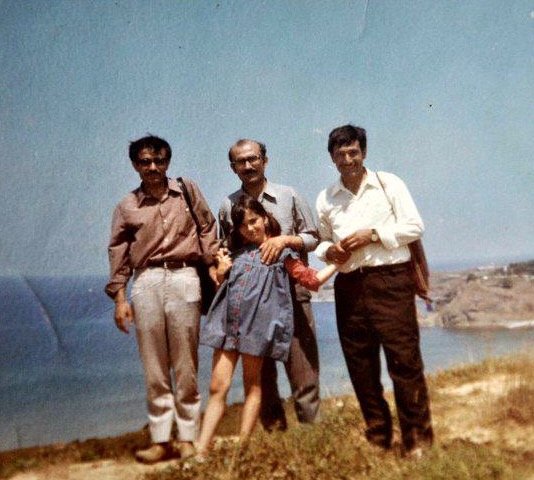

Top photo: Everyone has favorite parts of their story, and one of mine is that I’m the daughter of a Swiss mother and Turkish father, and the first in our family born in the U.S. This is me with three of my uncles in Turkey.